Chapter 6: Nino Frank and the film weekly Pour Vous: the first talking films

In November 1928, under the auspices of the important newspaper L'Intransigeant, Alexandre Arnoux launched a new cinema magazine, Pour Vous. Nino Frank wrote his first film article in the first issue of this magazine; and he was editor-in-chief there in June 1940, when it was closed down, along with its parent L'Intransigeant, at the onset of the German Occupation.

This very important film weekly of the period between the wars has received less than its due from later commentators, mainly because most issues disappeared and have only recently been re-united in a few film libraries (notably the Cinémathèques of Paris and Toulouse; the London BFI has only a very incomplete set). Many of its writers came together again in the equally important Écran français in 1945, where the foundations of postwar criticism – anglophone as well as francophone – were laid, before it was overtaken by the Communist orthodoxy of its owners in 1948.

The first issue of Pour Vous, of 22 November 1928, is of historic interest. The principles stated in it laid the foundations for a whole stream of serious French cinema journals, through La Revue du Cinéma and L'Écran français to the two journals founded in the 1950s and still continuing today, Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif. It was founded, along with its only near competitor, Cinémonde, at the moment of the arrival in Europe of sound film, and provides a record of the very negative reactions in French film circles at the release of the first talkies. The resistance to this development was more extreme in France than in any other country, especially because of the belief in cinema as an artform – the "septième art" – but also because of fears of loss of global influence; and a large part of the first issue of Pour Vous was devoted to vivid dissections of the birth-pangs of talking films.

First, in the opening pages of the magazine, Alexandre Arnoux described his vision, emphasising the title POUR VOUS, in something remarkably like a modern 'mission statement'. The front page trumpets:

POUR

VOUS

L'Hebdomadaire du Cinéma, 1 franc 50

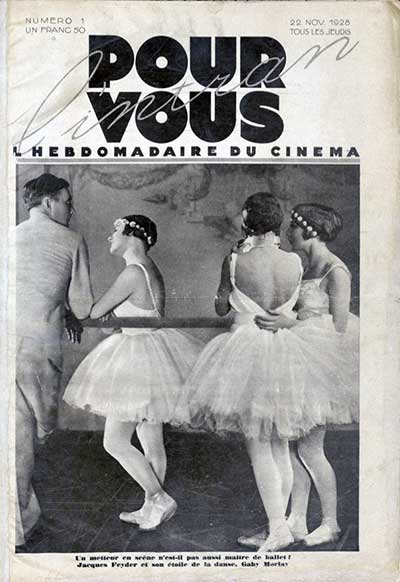

So this was not an expensive monthly or quarterly 'revue' for specialist cinema buffs, it was an affordable weekly for ordinary people. The full-page photograph below the title shows a famous director, Jacques Feyder, chatting informally with his star, Gaby Morlay, as they rehearse his latest picture:

"Jacques Feyder et son étoile de la danse, Gaby Morlay"

The whole second page was dedicated to a declaration of intent, again designed to reassure a lay public:

In English, this page reads:

And on page 3 the editors boldly stated that they would accept no cinema advertising, to ensure that they could always express freely their opinions of the films they reviewed, and of ongoing developments in the film world:

In this magazine our readers will not find a single line of film advertising, either overt or, more importantly, disguised.

We want POUR VOUS to remain independent. We want to express freely our thoughts on everything which concerns the screen, its authors, its artists, its producers, its backers, in short on everything which can serve the interests of France and also the art and industry of cinema.

Free of any attachment, any contract, any obligation of whatever kind, we will strive always to speak the truth.

POUR VOUS

It is a measure of the financial success of L'Intransigeant that Arnoux was able to persuade his masters to forego income from film advertising to help Pour Vous to pay its way. The vow was maintained throughout the whole 12 years of the magazine's life, and it was renewed after the war by the editors of L'Écran français, who had previously worked at Pour Vous.1 | orig

The impact of talking films

On this same page, Arnoux himself opened the discussion on talking films. In London, he had been to see The Terror (US, 1928, director Roy del Ruth), the first film with full dialogue to be shown in Europe. It was apparently not very well received, playing to half-full houses and closing after barely a month. A fundamental problem made itself felt: the loudspeaker, at a fixed point behind the screen, always projected the actor's voice from this point. To try to minimise this failing, the director placed the actors close together in static positions when a scene required speech, to monotonous effect. Worse were the exaggerated facial expressions imported from the theatre, especially in close-up scenes:

A woman screaming in horror, charging at me, and all I can see is a horribly grimacing black chasm, while the loudspeaker, still in the same place, shrieks from twenty feet away. I feel like a dentist in a nightmare, about to plunge into the wide-open mouth of a patient who has delegated to an understudy the job of screaming off-stage. 2 | orig

He admitted to a prejudice which would be widely acknowledged, especially in France, by directors and critics alike:

I love cinema deeply. The way it plays on black and white, its silence, the rhythms of its sequences of frames, the way it relegates the word, this ancient human bondage, to the background, seem to me the promises of a marvellous art. And now a barbarous invention is coming to ruin everything. Forgive me if I display a certain bitterness, a certain injustice...

But finally, he had to concede:

We cannot remain indifferent. We are present at a death or a birth, no-one can yet see which it will be. Something decisive is happening in the world of the screen and of sound. We must open our eyes and our ears.3 | orig

An interesting point of comparison is the contemporary review of the same film by C.A.Lejeune in London, making the same point as Arnoux' last paragraph, but in more positive terms:

May be crude, but it is a maker of history. Something has been achieved here. A new chapter of film evolution is beginning. Today it is as foolish to argue that talking films cannot be successful as to declare that a man in London cannot possibly speak by telephone to a man in New York.4

In order to give readers a preliminary grasp of some technical aspects (mainly disadvantages) of the new medium, page 4 of Pour Vous first issue provided articles by the 23-year-old assistant director Edmond Gréville on shooting the films and by G. Clairière on their production. The page featured two images of Al Jolson and The Jazz Singer, the first full talking film; as yet it had not been shown in Paris, but it goes without saying that the French were on tenterhooks to see it and pass judgment.

Gréville had been to London to watch the shooting of a new, talking film. His reactions, on this first exposure, are of key interest, as he represented the young generation which would shortly embrace the talkies wholeheartedly. Crucially, he was appalled by the practical difficulties facing the director of a talking film. He observed that unwanted background noise represented, both directly and indirectly, a very serious problem. The director could not give spoken instructions, and in fact:

he and the two cameramen were enclosed in a glass cage, and from the depths of this aquarium they flashed red or green lights to show the actors when they should start or finish their scene...the microphones have to be very sensitive. They are so much so, that when an actor pushes back a chair or puts a glass down on the table, you hear a noise like thunder. So you have to resort to trickery, you have to take extra care with every movement, and this leads to very inferior action sequences.

As Gréville went on to say, he was already convinced of the benefits of 'films sonores' – with background noises or music – and could see the possibilities of using the spoken word in documentaries and news; but for feature films, especially romantic ones, the technique was still too primitive and clumsy to be viable:

A new art could certainly be built on certain noises synchronised with images like trains, planes etc...I also firmly believe it would be worth introducing spoken words to the weekly news bulletins...for then these words have historical value: political speeches, Lindbergh's voice; but to hear Douglas Fairbanks say "Your eyes, my dear, make the stars go pale" – No!5 | orig

In the second article, Clairière described in some detail the various procedures on the market, the main ones being the American Movietone and Vitaphone, and the French Gaumont-Petersen-Poulsen. But for most readers the chief interest of the article must have been to read of the reception of American accents among English and European audiences, the difficulties of selling a film in one language in other parts of the world, and the problems of recording orchestras or large bands without deforming the musical sound. All the same:

...after producing a small revolution in the cinema, it won't take long for the talking film to settle down and calmly take the place, no doubt quite limited, which is suited to it.6 | orig[My italics]

Interview with Jacques Feyder, by Nino Frank

Pour Vous was a substantial magazine, 16 pages long, and Arnoux was conscious of the need for variety – of content, of style, of article length and type. When he recruited Nino Frank as one of his writers, it was the flair Nino had shown for interviewing writers for Les Nouvelles littéraires which the editor wished to harness for the dialogues he planned with directors, screenwriters and actors. The young man's assignment in the first issue shifted the register of the writing, here more human and more literary than the brief film reviews which preceded it. It was an interview with the famous director Jacques Feyder (already featured on the cover): a difficult interview, as the director was preparing to leave for America and did not wish to commit any indiscretions, which might be reported as he departed. All the same, Nino gained some clear impressions, both of his personality:

He's tall, slim, smiling. Thirty-five, perhaps. Dressed entirely in grey, elegant: blue eyes and a steady gaze. Alternating between hints and brutal directness, not hesitating to criticise the present state of affairs – as he's always done,

and of his opinions on the likely direction cinema would take, in this crucial period just after the appearance in America of the first talking picture, The Jazz Singer. As we have seen, at this time practitioners in France strongly favoured 'sound' films (i.e. those with only a background soundtrack) over 'talking films', because they felt that the former would retain more of the artistic quality of the best silent films, the 'cinéma pur'. The distinction made by Feyder here emphasises this supposed dichotomy and underlines the inferior image anticipated for talking films:

I'll arrive in Hollywood in the middle of the experiments in talking and sound films. I don't have any opinion on this, but I'll be forced to take an interest. When you think that two-thirds of investment budgets are being earmarked for these experiments! I think the tendency that will prevail will be that of making a clear separation between talking films and sound films, the first being restricted to those of a popular nature, intended for mass sales...Well, we'll see.

Especially interesting, given the deleterious effects the Hays Code would have on freedom of expression in American films from 1934 on, were his comments on the recent Howard Hawks film A Girl in Every Port – very popular in France, not least because of the presence of Louise Brooks – and the revelation that it was in France that the film had been censored:

Make no mistake, we shall have to revise all our judgments of the American cinema world: they have acquired a freedom both in the subjects they choose (think of A Girl in Every Port) and in the details, which they did not have before. Did you know that it was in France that A Girl in Every Port was "adjusted" a bit? Personally, I'm against all cuts, categorically.7 | orig

Thus a half-page interview has left for later generations a valuable historical insight into the attitudes of one of the most influential French directors during a period of fundamental change in the cinema.

René Clair on talking films

In the following years, the editors and contributors of Pour Vous continued to debate these questions – the direction of cinema in the future, the problem of censorship, the all-powerful situation of Hollywood vis-à-vis French cinema, and other serious concerns – alongside reviews of almost every film released in France. The fascinating debates are well worth following, and the complete run of the magazine, from November 1928 to June 1940, can be read on-line or downloaded from the website of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, via this link: https://www.lacinemathequedetoulouse.com/.

As early as May 1929 René Clair, in London at the time, was asked for his views on talking films, and gave as his firm opinion that the talkies were here to stay, and that the English film industry had embraced them almost as fervently as Hollywood:

So many billions have been spent on this enterprise that all possible means will be used to ensure its success. The talking film exists, and the sceptics who claim that its reign will be short may well not live long enough to see the end of this reign. This is no longer the time for those who love the art of images to deplore the effects of this barbarous invasion. Instead, it is time to cut our losses.

...Almost every day the newspapers devote long articles to the talkies, criticise, argue, praise, point out new inventions, ideas for projects, new companies being formed.8 | orig

Clair declared that he was impressed by the new Hollywood films Broadway Melody and Show Boat; and indeed, he would be one of the first French directors to embrace the talking film, with the famous Sous les Toits de Paris in 1930.

Nino Frank's contribution

Over the life of the magazine Frank wrote almost 1000 pieces for Pour Vous – reviews, articles, interviews, film summaries. During the first few months, before he began to divide his time between this work and running the revue Bifur (see previous chapter), he interviewed ten important directors and actors, and wrote gently mocking summaries of films of Josef von Sternberg (The Last Command), René Clair (Les deux Timides) and Buster Keaton (The General). The range of his interviews can be seen from a few quotations, from personalities who are largely forgotten today, but were serious players in the cinema of the time.9

An early interview is of particular interest, as it was with one of the few women directors of the time – Marie-Louise Iribe, who had recently completed Hara-Kiri, a film which has been given the label 'proto-feminist' by some modern commentators. It also illustrates the talent which made Frank a good interviewer – his ability to be the 'good listener' to whom people were happy to unburden themselves, providing insights for us now into situations and characters of the time. The excitable Iribe, who was both director and star of this daring film – the plot of which involved exotic locations, adultery and suicide – lashed out about the cuts directors were so often required to make, for commercial or political reasons:

I am pleased with Hara-Kiri. It was well received. Of course there were a lot of cuts, an enormous number of cuts. They always want more. How is a director supposed to cope, if he wants to reconcile the needs of his conscience and the demands of the producers? They grant you everything, money, agreements, and five minutes later, they ask you to make it more commercial...So how are you supposed to deal with this mess? I don't want to think the public is as stupid as that: it's a practical impossibility. "No violent death at the end, no long kisses, no cigarettes, no sadness..." and I don't know what else.

...And as for this idiotic censorship, what do you want me to say: I do not understand why what Humanité and public speakers have the right to write or say cannot to be seen on the screen.10 | orig

A further set of interviews demonstrates the value of strategically placed friends for gaining access to important names. Around the end of the year, the famous director Henri Fescourt was filming Monte-Cristo in the studios at Billancourt. The assistant director was Armand Salacrou, with whom Nino had become friendly through Max Jacob, so it was not difficult to obtain a pass to do some interviews on the set. Over the next few weeks, Pour Vous would publish three interviews: with the director, the established actor Jean Angélo, and the new young star Pierre Batcheff. Each had pronounced views about different aspects of contemporary cinema, but with a strong emphasis on 'sound' versus talking films, and a preference for the former.

Fescourt spoke passionately about the cinema, expressed serious doubts about talking film which he thought (as did others at the time) would be merely inferior theatre, but was enthusiastic about the potential for sound – which would be viewed as an extension of the art-form of silent cinema, not simply as appropriate background noise:

Cinema is the most splendid form of expression of modern art. Today a question of great importance, which interests me a lot, is that of sound and talking films. Well, I think that talking film – the reproduction of a theatrical spectacle, plus recording and dialogue – will be an abomination. But I have faith in the sound film. What we need to discover is how to use these discoveries to reinforce the expressive power of cinema...Think, if Léon Poirier had had at his disposal, when he was shooting La Croisière Noire, the means of recording, at the same time as the images, the countless silences and murmurings of the African forest!...And the very different sound qualities of ports like Amsterdam and Marseille! These horizons have no limits!11 | orig

When Nino went down to Billancourt to interview Jean Angélo, playing the eponymous hero of the film, he was struck by the strangeness of the world he had entered and thought it amusing to enlighten his readers on the reality of life in the studio. He described the uniform which was de rigueur for the crew on the set – a splendid pullover and magnificent cap – and for anyone else who wanted to appear a serious person with genuine business there. As he had found to his cost, turning up in a jacket, with a trenchcoat and hat, as you would in Paris, labelled you as an outsider and a figure of fun.

Nonetheless, he evidently succeeded in obtaining his interview. Jean Angélo, an experienced stage and screen actor, was the star, the Count of Monte-Cristo. He was happy to share his views about the current situation of cinema, though as a practitioner he was inclined to be dismissive of some of the more pretentious critical debates. He too came down firmly on the side of sound versus talking films, and also fiercely defended the virtues of cinema, giving an interesting analysis of the difference between cinema and theatre:

Ever since the day I started in films, I've been hearing talk about the crisis in French cinema. For as long as they've been killing it, it's kept going on. I think this is because a load of people suddenly discover the cinema and gravely tell you that it won't do at all. Ever since cinema was invented, we have obtained amazing results...As for the latest improvements, I am for sound films and against talking films; after all, silence is as atmospheric as noise. Cinema in colour is also a great idea. But the important thing is to go on making films: there is nothing more dissimilar than cinema and theatre. You can believe what I say, because I've worked in theatre too, for ten years. You see, cinema is outward expression of feelings, while theatre is, shall we say, internalization. They are the two faces of a single profession.12 | orig

Jean Angélo's opposite number in this film was Pierre Batcheff, playing Morserf. Russian by birth, handsome, with dark, haunted eyes, he was the perfect young star figure. When Nino was struck with the physical characteristics of his interviewees, he liked to describe them in detail, as here:

[On the set] Here is Morserf, slim, face tense and bitter, eyes darker and deeper than the black night...He turns towards us: his face is calmer, but his eyes are as black and romantic as before, with good reason. He looks slight in his chestnut frock coat, with his long narrow face, the lips of the young Don Juan, an abrupt laugh, quickly stifled, an unpredictable, staccato voice...Musset at eighteen. And the look, at the same time determined and vague, of a Byron. It is true that we are not in 1820. Nor, indeed, in 1860.

But Pierre Batcheff is like this. Pierre Batcheff is Morserf.13 | orig

This description is particularly poignant, as in 1932 the whole French cinema world was shocked when Batcheff committed suicide, at the high point of his career. But the haunted introversion of the tragic Romantic character is clearly prefigured here.

A move to "L'Intransigeant"

The freelance work for Pour Vous was going well, but did not bring in much money, and cracks began to appear in the administration of Bifur much earlier than Nino admitted in his memoirs years later.

A letter Blaise Cendrars wrote to him in 1929 shortly after publication of the first issue, evidently in reply to a letter he had sent, focuses on the fact that Nino's name had been omitted from the editorial list, although he had done a large part of the work (while in the case of the earlier revue "900", his contribution had been publicly recognised). Blaise had already refused to be a director of the publication because of the mismatch he perceived between the priorities of the rich bourgeois owner and those of the editors, and he was sceptical of its likely success. He wrote:

I agree absolutely with what you say. Perhaps it is better for you not to be named among the editorial body – and in playing this dirty trick on you, probably they'll prove to have done you a good turn.

He also had a practical criticism of the title typeface, which had a certain justification. The designer Cassandre's 'Bifur' typeface had recently been launched, and was much admired:

Anyway, why aren't they using the typeface invented by Cassandre and named 'Bifur', for the title of a revue called 'Bifur'??? Is it out of ignorance? If so, Bifur's claim to modernity is a hollow one.14 | orig

There was, of course, a reason. Pierre-Gaspard Lévy, the owner, had asked his friend Jean Lurçat to produce the design, rather against the wishes of the editors, who considered this choice to be their prerogative.

Already in autumn 1929, Waldemar George offered Nino an editorial job at the art magazine Formes, which he seriously considered, but a change in its ownership put paid to this prospect.

By the spring of 1930, when a shortfall in sales for the luxury revue with a leftwing agenda seemed to prove the editors right in their misgivings, Nino's belief in it was dwindling, and by the time that he was forced out in the autumn of that year, he was thoroughly disillusioned with the whole project. His efforts to gain other employment in the literary world were unsuccessful, but now L'Intransigeant, probably encouraged by Alexandre Arnoux, came to the rescue.

The successful newspaper L'Intransigeant ran a Saturday cinema page, of fairly limited interest, as most of its film writers were occupied writing for the subsidiary Pour Vous. When its staff writer Boisyvon (probably Lucien Boisyvon, who went on to write a number of books on the cinema) resigned to work on personal projects, the opportunity arose to shake up this page, make it more dynamic and encourage some of the Pour Vous writers to appear here as well. Alexandre Arnoux was evidently an important influence in making the change, and would go on to write a column on major films on this page for some considerable time. Almost certainly, he was also instrumental in recommending Nino to run the page, and on 14th February, 1931, the paper announced:

M. Alexandre Arnoux, the highly-esteemed writer who enjoys such authority in the cinema world, will give us – in complete independence – a review of the main films of the week. We have entrusted the editorship of the film section of L'Intransigeant to our colleague Nino Frank.15 | orig

Nino was evidently not wildly enthusiastic at the thought of the administrative work which would be involved in this job, on top of the reviews and articles he already wrote for Pour Vous and for L'Intransigeant itself. But he needed the money, as he wrote to his friend Alberto Carrocci at the magazine Solaria, on 24th February:

[I have gone] to take over the direction of the cinema page of L'Intransigeant, a change I've made entirely for financial reasons...Bifur is dead, the Revue de Genève too, and the journals which are well-disposed to me – only a few – are either just being started or are having to start again.16 | orig

It was time, then, for yet another change of direction, and an opportunity to clarify and broaden his thoughts about cinema, which in his mind had always come a poor second to literature. But now he would be obliged to become its champion.

All translations from European texts are my own.

[CLICK HERE to open notes in a new window]

Notes

1Pour Vous, no.1, 22.11.28, p.3.

2 Alexandre Arnoux, 'J'ai vu, enfin, à Londres un film parlant', Pour Vous, no.1, 22.11.28, p.3.

3 ibid.

4 C.A.Lejeune, quoted from Halliwell's Film and Video Guide, 2000 Edition.

5 Edmond Gréville, 'Toujours les films parlants...Comment on les tourne', Pour Vous, no.1, 22.11.28, p.4.

6 G. Clairière, 'Toujours les films parlants...Comment on les fabrique', Pour Vous, no.1, 22.11.28, p.4.

7 Nino Frank, 'Jacques Feyder va partir pour l'Amérique', Pour Vous, no.1, 22.11.28, p.7.

8 René Clair, 'Une enquête à Londres: l'avenir du film parlant', Pour Vous, no.28, 30.5.29, p.5.

9 For useful information on French cinema and its practitioners in the 1920s, see 1895, the Revue de l'histoire du cinéma published by AFRHC, the Association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma, supported by CNC, the Centre national de la Cinématographie.

10 Nino Frank, 'Marie-Louise Iribe, auteur de films, nous dit...', Pour Vous, no.5, 20.12.28, p.4.

11 Nino Frank, 'Un réalisateur français: H. Fescourt et son dernier film: "Monte-Cristo" ', Pour Vous, no.11, 31.1.29, p.9.

12 Nino Frank, 'Entre deux prises de vues, J. Angélo nous dit...', Pour Vous, no.12, 7.2.29, p.7. The sarcastic reference to negative commentators is almost certainly directed at literary critics like Georges Duhamel, who continued to decry cinema well into the 1930s.

13 Nino Frank, 'Un Russe naturalisé français par sa carrière: Pierre Batcheff', Pour Vous, no.6, 27.12.28, p.9.

14 Unpublished letter from Blaise Cendrars to Nino Frank, summer 1929.

15L'Intransigeant, 14.2.31, p.6.

16 Nino Frank, Lettere a Solaria, a cura di Giuliano Manacorda (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1979), letter to Alberto Carrocci, 24.2.31

Original quotations from which translations taken

(numbers match relevant endnotes)

1 Dans ce journal nos lecteurs ne trouveront pas une seule ligne de publicité notamment cinématographique, ni apparente ni, à plus forte raison, déguisée.

Nous voulons que POUR VOUS demeure indépendant. Nous voulons dire librement ce que nous pensons sur tout ce qui touche à l'écran, à ses auteurs, à ses artistes, à ses animateurs, à ses financiers, enfin sur tout ce qui peut servir l'intérêt français et aussi l'art et l'industrie du cinéma.

Libres de toute attache, de tout traité, de toute obligation quelle qu'elle soit, nous nous efforcerons de dire la vérité.

POUR VOUS

2 Une femme criant d'épouvante fonçant sur moi, et je ne vois plus qu'un gouffre noir horriblement contracté, tandis que le haut-parleur, toujours immobile, hurle à vingt pieds. Il me semble que, dentiste de cauchemar, je vais plonger dans la bouche grande ouverte d'une patiente qui a délégué une remplaçante pour pousser des clameurs à la cantonade.

3 J'aime le cinéma profondément. Ses jeux de noir et de blanc, son silence, ses rythmes enchaînés d'images, la relégation, par lui, de la parole, ce vieil esclavage humain, à l'arrière-plan, me paraissaient les promesses d'un art merveilleux. Voici qu'une sauvage invention vient tout détruire. Qu'on me pardonne quelque amertume, quelque injustice...

Nous ne pouvons rester indifférents. Nous assistons à une mort ou à une naissance, nul ne pourrait encore le discerner. Il se passe quelque chose de décisif dans le monde de l'écran et du son. Il faut ouvrir les yeux et les oreilles.

5 [le metteur en scène] et les deux opérateurs étaient enfermés dans une cage de verre, et du sein de cet aquarium, manipulaient des feux rouges et verts qui indiquaient aux acteurs à quel moment ils devaient commencer ou finir de jouer...les microphones employés doivent être très sensibles. Or, ils le sont tellement, que lorsque l'acteur déplace une chaise ou pose son verre sur la table, on entend un bruit de tonnerre. Il faut donc truquer, surveiller chaque geste, et il s'ensuit une infériorité terrible du jeu.

...un art tout nouveau pourrait se bâtir sur certains bruits synchronisés avec l'image telle que train, avion, etc...Je crois aussi fermement qu'il y aurait intérêt à adapter la parole aux actualités de la semaine, comme cela se fait en Amérique et en Angleterre, car alors cette parole a une valeur historique: discours politiques, voix de Lindberg: mais entendre Douglas Fairbanks dire "Vos yeux, mademoiselle, font pâlir les étoiles", non!

6 Il faudra peu de temps...pour qu'après avoir provoqué au cinéma une petite révolution, le film parlant y prenne tranquillement la place, sans doute assez limitée, qui lui convient.

7 Il est grand, svelte, souriant. Trente-cinq ans peut-être. Tout habillé de gris, élégant: des yeux bleus, un regard ferme. Tour à tour insinuant et brutal, et ne se privant pas de dénoncer les choses telles qu'elles sont. Comme il l'a toujours fait d'ailleurs.

Je vais tomber à Hollywood au milieu des expériences pour les films parlants et les films sonores. Je n'ai pas d'opinion là-dessus. Mais je serai bien forcé de m'y intéresser. Songez que les deux tiers des capitaux sont investis dans ces expériences. Je crois qu'il y a une tendance qui prévaudra, celle de séparer nettement les films parlants des films sonores, les premiers devant être seulement ceux d'un caractère populaire, destinés à la plus large vente...Enfin, on verra.

Persuadez-vous bien qu'il faut reviser tous nos jugements sur le monde cinématographique américain: ils ont acquis une liberté, dans les sujets (songez à A girl in every port), dans les détails, qu'ils n'avaient pas auparavant. Savez-vous que c'est en France qu'A girl in every port a été un peu "arrangé"? Moi, je suis contre toutes les coupures, délibérément.

8 Sur cette entreprise est jouée un si grand nombre de milliards que désormais tous moyens seront bons pour assurer sa réussite. Le film parlant existe et les sceptiques qui prétendent que son règne sera court ne vivront peut-être assez longtemps pour voir la fin de ce règne. Il n'est plus temps pour ceux qui aiment l'art des images de déplorer les effets de cette invasion barbare. Il s'agit plutôt de faire la part du feu.

...Les journaux consacrent presque chaque jour de longs articles aux talkies, critiquent, combattent, louent, signalent de nouvelles inventions, des projets inédits, des sociétés naissantes.

10 Moi, je suis contente d'Hara-Kiri. On l'a bien accueilli. Il y a bien entendu, beaucoup de coupures, énormément de coupures. Ils en veulent toujours davantage. Comment voulez-vous qu'un réalisateur se tire d'affaire, s'il veut concilier les exigences de sa conscience et celles des exploitants? Ils vous accordent tout, argent, autorisations, et cinq minutes après ils vous demandent de commercialiser davantage...Alors qu'est-ce que vous voulez qu'il en sorte? Je ne veux pas croire que le public soit si bête que ça: c'est matériellement impossible. "Pas de mort violente avant la fin, pas de longs baisers, pas de cigarettes, pas de tristesse..." que sais-je et ce n'est pas tout.

...Quant à cette interdiction idiote, que voulez-vous que je vous dise: je ne comprends pas pourquoi ce que l'Humanité et les orateurs ont le droit d'écrire ou de dire, ne puisse pas se voir sur l'écran.

11 Le cinéma est le mode d'expression le plus splendide de l'art moderne. Il y a aujourd'hui une question, d'une très grande importance, dont je me suis beaucoup intéressé, celle des films sonores et parlants. Eh bien, le film parlant, reproduction du spectacle théâtral, enregistrement et dialogue, je crois que ce sera quelque chose d'abominable. Mais j'ai foi dans le film sonore. Ce qu'il faut trouver, c'est l'utilisation de ces découvertes en vue de renforcer la puissance expressive du cinéma...Pensez si Léon Poirier avait eu à sa disposition, quand il tournait La Croisière Noire, le moyen d'enregistrer en même temps que les images le silence innombrable et les murmures de la forêt africaine!...Et les sonorités si différentes de ports tels qu'Amsterdam et Marseille! Il y a là des horizons illimités!

12 Du jour où j'ai commencé, j'entends parler de la crise du cinéma français. Depuis le temps qu'on le tue, ça dure toujours. Je crois que ça dépend d'un tas de gens qui découvrent tout à coup le cinéma et qui vous affirment gravement que ça ne va pas du tout. Depuis que le cinéma est inventé, nous avons obtenu des résultats formidables...Quant aux derniers perfectionnements, je suis pour le ciné sonore et contre le ciné parlant; après tout, le silence est aussi impressionnant que le bruit. Le ciné en couleurs aussi est une grande idée. D'ailleurs, l'important c'est que l'on fasse toujours du cinéma: rien de plus dissemblable que le cinéma et le théâtre. Vous pouvez m'en croire, puisque j'ai fait aussi dix ans de théâtre. Voyez-vous, le cinéma, c'est l'extériorisation des sentiments, tandis que le théâtre en est, comment dire, l'intériorisation. Ce sont les deux faces d'un seul métier.

13 [Sur le plateau] Voilà Morserf, mince, la figure contractée et amère, les yeux plus sombres et plus profonds que la nuit noire....Morserf fait demi-tour: sa figure s'est apaisée, mais ses yeux sont aussi noirs et romanesques qu'auparavant, et pour cause. Il est mince dans sa redingote marron, avec un visage étroit et long, des lèvres de Don Juan jeune, un rire qui s'éteint vite, une voix capricieuse, par à-coups...Musset à dix-huit ans. Et le regard volontaire et vague à la fois que devait avoir Byron. Il est vrai que nous ne sommes pas en 1820. Ni en 1860, d'ailleurs. Mais Pierre Batcheff est ainsi. Pierre Batcheff, c'est Morserf.

14 Il vaut peut-être mieux pour vous de ne pas figurer dans l'équipe directrice - et en vous faisant une vacherie, on vous rend probablement service –

...Pourquoi, par exemple, ne pas employer le caractère d'imprimerie inventé et dénommé par Cassandre 'Bifur' pour le titre d'une revue qui s'appelle 'Bifur'??? Est-ce par ignorance? alors la cause moderne de Bifur est jugée!

15 M. Alexandre Arnoux, l'écrivain si estimé et qui jouit d'une si haute autorité dans le monde du cinéma, nous donnera chaque semaine, en pleine indépendance, une critique des principaux films. Nous avons confié le secrétariat général de la rubrique cinématographique de L'Intransigeant à notre collaborateur Nino Frank.

16 ...per prender la direzione della pagina cinematografica dell'Intransigeant, mutamento fatto unicamente per ragioni di denaro. Bifur è morta, la Revue de Genève anche, le riviste mei amiche - un paio - son lí da nascere o da rinascere.