Ivan Goll and L'Eurocoque (an English translation)

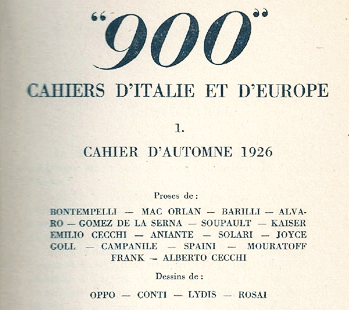

In 1926, the Alsatian writer Ivan Goll published a short story, L'Eurocoque, in the new literary journal "900", created by an Italian publisher but written in French and edited in Paris by Goll's friend Nino Frank. The journal was the brainchild of Massimo Bontempelli, who hoped to introduce new young Italian writers to a wider readership by embedding them in a publication which also featured avant-garde writers from throughout Europe. In this story Goll depicted what he saw as the internal degeneration and decay of western civilization, through the metaphor of a bacillus (the 'euro-coccus') which destroyed its victim from the inside, leaving only a hollow shell.

He developed the theme into a German-language novel, Die Eurokokke, in 1927, and revisited the subject twice in French, in Sodome et Berlin (1929) and Lucifer vieillissant (1934).

There is considerable interest in Goll today, especially in Germany where he is seen as a major Expressionist writer of the between-wars period, but also in America, where the metaphor of a Europe drained of energy and ambition is sometimes thought to have continuing relevance. As far as I know, neither his original story nor his novels on this subject have been translated into English, so for the benefit of English-language readers I offer below an adaptation/free translation of the 1926 short story L'Eurocoque.

L'EUROCOQUE [THE EUROCOCCUS]

I was walking down the Avenue de l'Opéra, among the millions of other useless slobs who, all fitted out with bowler hat, raglan-sleeved wool-mixture overcoat and calf leather shoes, were obstructing this splendid road, crammed together like a spoonful of caviar on a slice of bread. I myself was only a sad grey globule, yet I clearly believed in my importance, since I was always calling on Fate with a capital 'F'. And all these beings, who passed so uncomfortably close to me, with raucous and ignoble shouts, with hostile and stupid looks, were also all day long calling on Fate to help them.

Had my curse been effective so soon? Suddenly, from a nearby street, a woman appeared who seemed to be suffering from extraordinary agitation. She was running, pointing, shouting. At the end of her right arm, like a big white bird, she brandished the evening paper, trying to sell it for 10 centimes, to make a profit of 2½ centimes per copy. To attract the attention of the deaf-and-dumb crowd, she bawled out in a tinny wail: "Attack on the Paris-Rome Express!"

I read: Three young men, one of whom bore MY name, had smuggled themselves, 130 kilometres before Paris, into a first-class coach of the famous Express: while two of them guarded the entrances, the third, I MYSELF, with a Browning automatic at the ready, visited all the compartments and calmly emptied wallets and cases. But an old officer, who had had the stupid idea of defending himself, since he still believed in divine retribution, was killed by a single little bullet. The assassin had the definite feeling that he was carrying out an act which was important even though hardly necessary. At that moment, the train slowed down because of repairs on the track, allowing the three bandits to jump and land on their feet in a field of rye glowing pink in the dawn, among the cicadas and the poppies. A terrified lark flew upwards to broadcast to the entire world the news of the attack. But before the gendarmes had picked up their sabres and helmets, the young men seized a military truck on the road, and arrived in the suburbs of Paris ahead of the Express. The last traces of the one who was ME were found in a little café in Pantin, where he had ordered a six-egg omelette and a litre of white wine: but he had disappeared without tasting them.

This is the description of the leading criminal:

Unruly hair. Sensual mouth. Hollow-eyed from gazing at the stars, during long sleepless nights. Badly-knotted tie. Dangerous appearance, like in a passport photo. Lemon-yellow gloves.

This was very precise: it was certainly me. I looked at myself in a jeweller's window and recognised myself. For the first time for ages, I felt alive. I had been vegetating in the soundproof cellars of boredom; now I realised it.

Lemon gloves. I felt my hands grow heavy and swollen as in some of Picasso's paintings. I must take them off, these dangerous gloves, but I had neither the courage nor the ability. They were sticking to my hands. The passers-by couldn't take their eyes off them. To have removed them in the street would most certainly have given me away! My hands had become the focus of attention of the whole Avenue: some people were looking at them with astonishment, others with indignation, a few with pity, but most with admiration.

What was happening? Was I about to be arrested? As I started to cross the Rue des Petits Champs the traffic policeman, noticing my lemon gloves, solemnly raised his white bâton and stopped a raspberry-red Panhard and an official Ministry of Finance car, to allow me to cross. A woman, who must have been a rich Cuban from the Ritz, turned her green eyes first to my hands, then to my eyes, and scenting the crime, signalled to me to follow her. Ordinary people stared at me, searching in my face for a resemblance, but to whom? My lemon gloves leapt out, in the middle of the Avenue de l'Opéra, and everyone was holding a copy of the newspaper which pointed to me. What, then, was this immunity I was enjoying?

At all costs, I wanted to get the gloves off my bloodstained fingers. With this aim, I entered a café, wanting to take them off in the doorway. But it was a revolving door, which turned continuously. After being swept round at a run three times, I had not yet succeeded in undoing a single glove-button. So I was forced to walk, with the damning exhibits on my hands, past rows of bald heads and tulle-bordered hats, and lips which whispered anxiously: "Unruly hair...badly-knotted tie...lemon gloves..."

Finally I reached a little marble table, right at the back of the room, backed on to a pillar. I thought I was alone. Suddenly, the head of a scholar, with grey beard and gold-rimmed glasses, came towards me from behind the pillar. The old man screwed up his left eye and took one of my hands, which I had just hidden under the table, to relieve it, finally, of the glove. He took out of the pocket of his jacket a microscope with three extending tubes, like those used by salesmen in the silk trade, put it on my glove and studied its sinews for a long time, then rolled it up and began an examination of the palm of my hand. Frozen with fear, I neither dared to remove my hand, nor to utter a word. But suddenly the man let it go, stood up and called out in a portentous voice: "The Eurococcus! I've found it!"

Nobody in a café pays attention to a man who appears to be mad. Straight away he sat down again beside me and, seeing my pallor, burst into tears and poured out his story:

"My dear Sir, you must be the most unhappy man in Paris. But one day you will be the most celebrated person of our century. You are the first European attacked by the eurococcus!

The Eurococcus, Sir, is the phylloxera of European civilization, or more precisely, the civilization of the West. It is the microbe which is preparing the death of this continent. I am a Professor of Chemistry at the University of Philadelphia, but for the last ten years I have been living in Europe and researching the microbe which is consuming you.

First of all, I found the eurococcus on the towers of Notre Dame. These are more diseased than any other historical monument, more than the Pyramids, the Strasbourg Minster, or the tombs of Prague Cemetery. Externally, not a sign: neither cracks nor holes! But the stone is blackened right through to its core, it has lost its weight and its substance, now it is no more than a sponge soaked in the smoke and tears of the city. Notre Dame, my dear Sir, no longer exists except in our imagination. It is a chimera of a construction which no longer represents faith, or God, or anything. The eurococcus has destroyed it.

A little later, I discovered the microbe on a fifteenth century quarto text which I had bought on the quays of the Seine. At first, nothing unusual appeared. The yellowed paper, spotted with brown stains, sheltered a really glorious collection of parasites: worms and aphids which, below the binding, had dug out a system of canals and shady avenues. But after long, patient work, I finally recognised the eurococcus. And the book, by one of our great classical writers, had lost almost all its significance. It had been emptied of its spirit. The sentences no longer had any meaning. The book weighed only 29 grams now, and was losing 12% of its value every year. The eurococcus, I repeat, eats away interior value and wipes out the spirit of things.

Long years passed before I was able to identify the eurococcus on an animal. You'll never guess which one taught me the ultimate lesson about our civilization: a donkey. It belonged to one of these rag-pickers ['chiffonniers'] who, between two and seven in the morning, do the rounds of Paris and go through the secrets of men hidden in their rubbish. Probably they are the ones who understand the greatest number of truths about life. But they keep their silence, and no-one ever sees them. They are almost invisible beneath their rags, behind the mask of wretchedness. They work like maniacs in the freezing underworld of the streets. Sometimes, tipping out buckets which are too full, they awaken frightened sleepers. Starting up in their beds, these people understand for a second that somewhere unknown forces are acting against them. But they always go back to sleep and leave their sad, vain secrets in the hands of the wretches. There was a time when, at these metaphysical hours of the night, there rose up the voice of a donkey harnessed to the cart of a rag-picker, of whom it is said that his trade brought him a villa in Auteuil. This voice of wood and metal, this mournful, strident voice, expressing all the distress of the sleeping world, was as terrible as that of the condemned men in the ships and of the prophets in the gardens of the kings, the voice of reason and misfortune.

One day, after braying out into Paris the longest and most mournful cry of its life, the donkey collapsed on the asphalt. Neither whipping nor kicking would bring it back to life. And yet, it was not dead. The rag-picker took it to a veterinary doctor on the Quai Bourbon, where I happened to be. And together we made this discovery: the donkey no longer consisted of anything but leather and carcass, its ears and the skin of its back being even tougher than its bridle. But inside, it no longer had lungs, or bowels, or spleen. It had been emptied, eaten away by the eurococcus...

Since then, I have succeeded in identifying the microbe. The form it takes varies with different objects and beings. I had never yet found it on a man. And now, here it is on your hand! The human eurococcus. Let me embrace you, my dear Sir. You are rendering an outstanding service to humanity.

No doubt, in the same way as stones, books and donkeys, you have been completely emptied inside. Perhaps you no longer have either heart or liver. You seem very unhappy. You no longer have any ambition, or any pleasure. You are so bored, so bored! Through pure boredom you would be capable of anything at all, because no duty to the world, no reason, no respect, no responsibility, no faith restrain you. You have the "emptiness sickness". Look, this bandit from the Paris-Rome Express might well be you..."

Postscript. During the 1920s many of Goll's European and British contemporaries thought that America would provide the energy and innovation to save the West. Goll was not convinced. In a 1928 series of articles on European views of America, in Eugene Jolas's journal Transition, no.13, pp.255-256, he said:

"For you Americans, Europe is no longer anything but a beautiful poetic windmill whose immobile arms stretch out towards a symbolic twilight. We are a museum full of inestimable riches...Certainly, Europe is dying of senility, of the 'eurocoque'. But your pill 'Americoon' has nothing in it but bicarbonate of soda, and cannot serve us as an elixir. Americans, leave us alone! Let us die our death!"

Ivan Goll in the launch issue of "900" [Novecento/Twentieth Century]

The first issue of "900" came out in October 1926, and its Table of Contents is shown above. Nino Frank, who was acquiring a reputation for his word-portraits of contemporary writers and artists, wrote a section of "900" entitled 'Astérisques' - short sharp comments on contributors and other writers, interspersed with ironic or amusing maxims about Paris society. In this issue, he included a character-sketch of Goll. It is helpful, before reading this, to be familiar with the background to the writer's work:

Ivan Goll was born in Alsace in 1891, and belonged to one of the unfortunate generations of French people who lived in Alsace under German rule, and never felt totally French or German. His Jewish heredity also made life more difficult for him. His early years were spent in a French-speaking community, but after his father's death he moved to Metz with his mother, to a German-speaking school. With the outbreak of war in 1914 he fled to Switzerland, to avoid being conscripted to fight against France. There he was involved with Dada and early manifestations of Surrealism, and in experimental poetry forms, including cubism. In the 1920s he lived mainly in Paris with his wife Claire, mixing in international literary circles and publishing in both French and German, but by 1933, when Die Eurokokke was burnt in Berlin, it was no longer safe for him to travel in Germany. He never truly belonged anywhere, and wrote of himself as 'Jean sans terre', a stateless wandering Jew.

This is how Nino Frank described him:

Ivan Goll, the man who sings his way through life. Impossible to miss seeing that he is German. He has a laugh the colour of the Rhine. Glasses which magnify his eyes, glinting like the lights of the Nuremberg Festival, in the night of fantasy. Impossible to miss seeing that he is French. He is full of smiles, and of market-stall irony. His eye fixes on every new spectacle, and gives him an excuse to forget how to write verses: he thinks up mysterious new theories about the universe.

My dear Robert Delaunay, keep an eye on Goll; he's the man who one of these days will steal the Eiffel Tower from you, and spirit it away.

But where?

Note

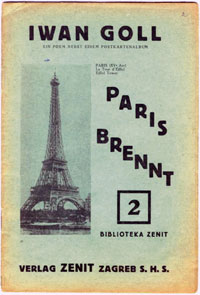

Robert Delaunay (who was a friend of Goll) had established himself as the painter of the Eiffel Tower, with a series of paintings between 1909 and 1914, and a return to the subject in the 1920s. Goll had published in the Zagreb journal Zenit in 1921, with a picture of the Eiffel tower, a long experimental poem, 'Paris brennt'. He brought out a French version in 1923, 'Paris brûle', and a German volume, containing the same poem but with the overall title 'Der Eiffelturm', in 1924.

Robert Delaunay (who was a friend of Goll) had established himself as the painter of the Eiffel Tower, with a series of paintings between 1909 and 1914, and a return to the subject in the 1920s. Goll had published in the Zagreb journal Zenit in 1921, with a picture of the Eiffel tower, a long experimental poem, 'Paris brennt'. He brought out a French version in 1923, 'Paris brûle', and a German volume, containing the same poem but with the overall title 'Der Eiffelturm', in 1924.

For a more general account of the launch of "900", see Chapter 2, Nino Frank and the Italian journal "900", on this website.